The Holographic and Fractal Universe

I remember when I was around 15 years old in high school, sitting in the classroom during one of my very first chemistry lessons. The teacher — Mr. Altenberg — was discussing the structure and composition of atoms, having a small nucleus in the center and a few electrons swirling around it. He made a rough sketch of it on the blackboard. And at some point I interrupted him and I asked him: “Mr. Altenberg, that drawing looks a lot like our solar system. Isn’t it possible that our solar system is perhaps just an atom in a much larger structure in the universe?” Mr. Altenberg, certainly among one of the cooler teachers I’ve ever had, looked away, stared for a second, and then slightly to my surprise admitted that it was a possibility.

But that was not the first time I had wondered about this. Much earlier during my childhood, while reading books on astronomy with pictures depicting our solar system, I remember always thinking that our solar system looked so much like an atom. It seemed so obvious to me, and I wondered if anyone else had the same thoughts I had because I had never seen that mentioned anywhere else. And I thought that if we could just zoom out of the universe enough, we might discover that we’re really living on an electron in a molecule inside a cell of a much larger living organism. Similarly, every cell in our body could be home to an infinite number of universes packed with electrons capable of supporting life just like our planet Earth. And as it turns out, research in the last 80 years shows that I wasn’t so crazy for thinking this after all. And neither was Mr. Altenberg.

Much later when I was around 17 years old and I had a personal computer at home, I got a program on a floppy disk from a friend that could draw the Mandelbrot fractal set onto the screen. The Mandelbrot set is named after mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot who was the first to visualize it using the computer technology he had access to while working at IBM in the 1980s. I was fascinated by the Mandelbrot set because it was obvious to me that what I was seeing on screen was similar to viewing a universe from the outside. I could zoom in and out of it continuously and I spent quite a lot of time going on adventures by zooming in to the tiniest parts of the whole set which constantly revealed new beautiful and complex details. It was almost as if I could visit new worlds existing within, and being part of, a much larger world. In a documentary on fractals by Arthur Clarke (“Fractals – The Colors of Infinity”) linked below you can see at around 5 minutes and 20 seconds in what it’s like zooming into the Mandelbrot set. This sequence is pre-recorded, but there are also programs available on the Internet (here’s a free app for Windows 8 that I love made by Rudi Chen) where you can interactively click and zoom in exactly on which part of the set you want, allowing you to freely explore the “Mandelbrot universe.”

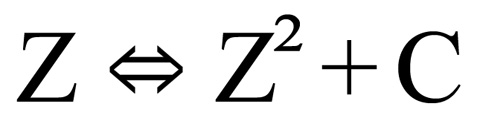

When you view any fractal set, you’ll notice that after a view magnifications the patterns start repeating again albeit with slight differences and decreasing or increasing complexity. This self-similarity is one of the important characteristics of fractal patterns. You can recognize the whole in the tiniest parts of the pattern and vice versa. But it’s important to note that no matter how complex the patterns you’re looking at may be, they’re the result of a relatively simple elementary equation. In the case of the Mandelbrot fractal set, for example, seemingly infinite complexity is achieved with a very simple looking equation:

Pay special attention to the double arrow equal sign. This is very important because it signifies the recursive nature of fractals, and the fact that there’s a built-in feedback loop. This simple equation, given enough iterations, can produce patterns that look as complex and as beautiful as the image below:

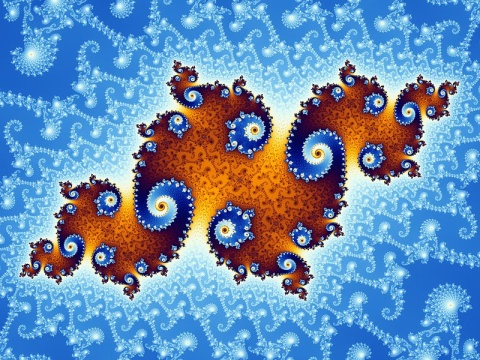

Partial view of the Mandelbrot set (Source: Wolfgang Beyer)

Looking at this image, you might say to yourself that there’s no way such a complex and organic looking pattern could be created using a simple mathematical formula. But the fact is that it was, and the cool thing about this is that we’re now finding that the same thing can be said about nature.

When we look at the world we live in, we see complexity and diversity. And at first you wouldn’t expect such random and chaotic looking patterns to be defined by a mathematical formula. Take trees or mountains for example, or the way rivers branch out. And yet what Benoit Mandelbrot found is that even such seemingly random, chaotic and complex looking patterns can all be described using relatively simple mathematical equations. Simple equations that create a basic pattern but through many iterations produce complex and detailed looking structures. Today such equations are used to simulate nature in very realistic looking computer generated worlds. Users of 3D imaging software such as 3D Studio Max will be familiar with using fractals to simulate things like clouds or mountains. All of this is explored in detail in a documentary by PBS/NOVA titled “Fractals – Hunting the Hidden Dimension” (YouTube link) which I highly recommend checking out for a much more detailed understanding.

For years scientists have been trying to find a single equation that could describe our entire universe. Albert Einstein spent his last days trying to come up with such an equation but ultimately couldn’t finish his work. Even the legendary Nikola Tesla spent his last days alone in his hotel room working on his own theory to describe the universe, but was unable to finish his work. That such an equation exists is a certainty; the only thing that’s not so certain is if we’re ever going to be able to find it ourselves. We can however see this equation expressed everywhere around us in nature in various iterations and levels of magnifications with a high degree of self-similarity — which is what you’d expect from a fractal pattern. Many ancient civilizations have known this even thousands of years ago and have encoded this knowledge in what is now known as “sacred geometry.”

The golden ratio (Phi), for example, is a geometric relationship that is found everywhere in nature and appears to be a product of the basic equation that describes our universe. Just like you can look at the Mandelbrot fractal set and see similarities and relationships between pieces of the pattern everywhere, so too can you look at nature and see similarities and geometric relationships everywhere.

The golden ratio in nature

The short video clip below titled “Nature by Numbers” which is available on YouTube does an excellent job at explaining this relationship visually.

In the below image of a cauliflower you can not only see the golden ratio expressed in the spiral distribution, but you can also see the fractal nature of the structure with repeated self-similarity at various levels.

Cauliflower

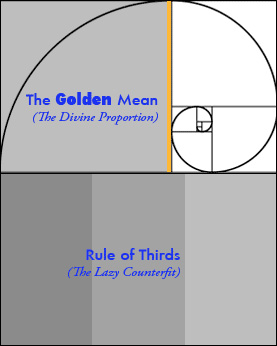

The golden ratio can even be found in the design of the human body. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci have known about this geometric relationship in nature for centuries and you can find it expressed in many popular artworks. In photography for example, a popular rule for creating a visually appealing composition is the Rule of Thirds which is also based on the golden ratio. Photographer Jake Garn explains it here:

That brings me to the Rule of Thirds. After a tremendous amount of research (I read a book) I learned that the rule of thirds may actually be just a lazy man’s sham. That’s right, I said it… a lazy sham! On the surface the rule of thirds doesn’t really make a ton of sense, I mean why would a composition broken up into three equal parts be innately more appealing than any other random spattering in a composition? Well what if I told you that nature actually does instinctively, and inexplicably seem to have a naturally occurring preference towards a specific ratio, a peculiar number, a divine ratio if you will?

To find the real story behind the “rule of thirds” we need to go back in time, not to the renaissance, not to the Greeks, and not even to Adam nor Eve… even further. We need to go to the creation of the universe, why is that? Well I’ll tell you why. There is a number that determines how a sunflower’s seeds grow, it determines the path a hawk takes when diving at it’s prey, it is echoed in the breeding habits of rabbits and it even determines how the spirals in a spiral galaxy are laid out. It’s all very simple in it’s beauty and best of all, it’s all true. If you want to wrap your head around it further then I highly recommend the book The Golden Ratio by Mario Livio.

As an aside, this reminds me of the time when I criticized Canon Inc. for not thinking about the rule of thirds when designing focus systems on their cameras. You would think that a serious camera manufacturer would pay attention to such natural and elementary rules of composition.

The realization that nature — our entire universe — is a fractal, opens the door for us to new realizations and understandings about life and the world we live in. By applying this realization to various problems in science, we can develop better solutions much faster. An example of this is the exciting research that’s being done by Nassim Haramein, where he uses this understanding of fractals and geometric relationships in nature to develop his new unified fields theory. I highly recommend checking out the below presentation (at the “Nexus Conference, Australia, July 2010”) by Nassim (also available on Archive.org), which will not only entertain you, but is guaranteed to blow your mind. Nassim Haramein’s paper titled “The Schwarzschild Proton” was accepted by a panel of 11 peer reviewers at the University of Liege in Belgium and won the best paper award in the fields of physics, quantum mechanics, relativity, field theory and gravitation. In my opinion Nassim could be the Albert Einstein of our time.

What Nassim shows in his presentation is exactly what I always wondered during my childhood: That our universe may be a gigantic, seemingly infinite, fractal structure where you can zoom in and out as much as you want and continue to be able to find the whole expressed even in the tiniest parts over and over again. And I said “seemingly infinite” because even though our universe may appear to be infinitely large, and we may be able to zoom in and out infinitely, it may still occupy a finite amount of space and thus be finite. If you can’t imagine how this is possible then don’t worry; in the beginning of the above linked presentation, Nassim explains how a finite space can contain or encapsulate an infinite space. Interestingly this same illustration also shows how we can all be individuals living in this universe and still be connected to each other and be a part of a whole. Single individuated pieces of consciousness that are part of a much larger consciousness, as physicist Thomas Warren Campbell explains in his book trilogy “My Big TOE (Theory of Everything)” which I also highly recommend as it fits in nicely with Nassim’s work.

What this means is that the spiritual teachers from the past were always right when they said that we all contain the universe or infinite possibilities within ourselves, and if we want to find answers we have to look within ourselves. Indeed each and every one of the atoms in our body enfold the entire universe within them. And now we’ve come to a point where this isn’t just theoretical metaphysical talk, but hard scientific fact as Nassim explains in his presentation.

For years science has been trying to find a single theory of everything — one mathematical equation that could describe the entire universe. But their approach is far too complex and based on the wrong assumptions, and it’s no wonder that string theory keeps them busy for so long without any kind of significant progress. Perhaps they need to go back to the basics and instead of describing the complexity, describe the simplicity that lies at the basis of all the complexity we see around us. Instead of looking at our whole universe, we need to go back and look at the elementary structure that lies at the base. Once we *really* understand that, it will be easier to understand how it scales up to form the more complex structures we see around us. It’s like researching how a single cell in the human body functions, in order to understand the workings of our body as a whole. Because like artists and philosophers from hundreds of years ago have known (and Leonardo da Vinci was one of them), even the human body is based on a fractal design.

However, all of the above gets even more exciting when you realize that the fractal nature of our universe is one of the defining characteristics of a hologram. Research in the last 80 years increasingly points to the fact that we might be living in a holographic reality and the fractal nature of our reality is just one evidence of this. Certainly Nassim Haramein’s research would support such a concept and the fact that our universe may be a virtual holographic reality is the basis of Thomas Campbell’s research as detailed in his book trilogy “My Big TOE”. David Icke has also been talking about this for years, and in his book titled “Infinite Love is the only Truth: Everything Else is Illusion” he also spends a lot of time on this subject. But the book I would really recommend you check out is “The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of Reality” by Michael Talbot.

In an article on Rense.com, Talbot describes one of the important features of a hologram:

To make a hologram, the object to be photographed is first bathed in the light of a laser beam. Then a second laser beam is bounced off the reflected light of the first and the resulting interference pattern (the area where the two laser beams commingle) is captured on film. When the film is developed, it looks like a meaningless swirl of light and dark lines. But as soon as the developed film is illuminated by another laser beam, a three-dimensional image of the original object appears. The three-dimensionality of such images is not the only remarkable characteristic of holograms. If a hologram of a rose is cut in half and then illuminated by a laser, each half will still be found to contain the entire image of the rose. Indeed, even if the halves are divided again, each snippet of film will always be found to contain a smaller but intact version of the original image. Unlike normal photographs, every part of a hologram contains all the information possessed by the whole.

The “whole in every part” nature of a hologram provides us with an entirely new way of understanding organization and order. For most of its history, Western science has labored under the bias that the best way to understand a physical phenomenon, whether a frog or an atom, is to dissect it and study its respective parts. A hologram teaches us that some things in the universe may not lend themselves to this approach. If we try to take apart something constructed holographically, we will not get the pieces of which it is made, we will only get smaller wholes.

While it is true that if you would cut a hologram into a few pieces, you could still view the entire image by illuminating a single piece, the resulting projection would be of a lower resolution. Talbot mentions in his book that the projection will get hazier and smaller. So it’s important to understand that although the whole image can be found on each individual piece, it’s of a much lower resolution compared to the original bigger piece because of less detailed information being available. This brings me back to the point I made earlier that if we want to understand our reality, it would perhaps be smarter to look at the elementary structure that lies at the base, which is much simpler, and then try to work out how that scales up. In the example of the hologram, a small piece of it contains much less information compared to the whole, but is still a reflection of the whole. Thus it may be an easier way to understand the whole. If instead we try to understand our universe at the macro level, it may be far too complex to get an accurate grasp of it and theories we work out based on that may not hold true as we scale up or down. This is exactly what scientists are now seeing; Newton’s laws do not hold up in the world of small particles. And that’s because they are grossly incomplete and inaccurate and cannot describe reality in general; they work only for a very small subset of reality. It’s no coincidence that the science related to small particles — quantum mechanics — is found to be able to give us a much better understanding of our reality.

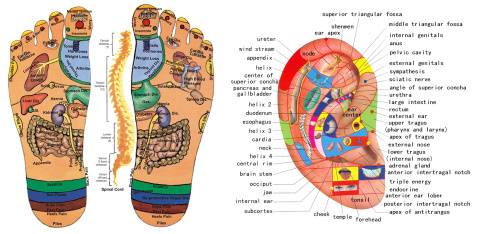

I had already mentioned that the human body also has a fractal design and this is explained by the fact that the human body is also a hologram, itself existing in a much larger hologram we call our universe. Just like in a hologram, you can find the whole human body in each part of the body too. Not only that, but everything is also fundamentally interconnected and part of the larger whole. Acupuncture for example is based on this principle. In the image below you can see the acupuncture pressure points on the feet and the ear which are connected to various other parts of the body.

And of course we know that each individual cell in our body contains its own copy of our DNA which contains all the information to describe the whole body. It’s mind-blowing to realize that when you look in the mirror and see the complexity of your body in front of you, all of that information is enfolded in a small strand of DNA in a single cell in your body. And just like with a fractal pattern, through billions of iterations this small piece of information develops into the complexity that is you. In fact the very way we procreate is of a fractal nature.

In the beginning of Nassim Haramein’s presentation, which I linked above, he beautifully illustrated how certain parts inside a fractal structure can appear to be separated from each other while still being fundamentally interconnected. Physicist David Bohm, who was a protégé of Albert Einstein and one of the world’s most respected quantum physicist, said the same thing:

In 1982 a remarkable event took place. At the University of Paris a research team led by physicist Alain Aspect performed what may turn out to be one of the most important experiments of the 20th century. You did not hear about it on the evening news. In fact, unless you are in the habit of reading scientific journals you probably have never even heard Aspect’s name, though there are some who believe his discovery may change the face of science.

Aspect and his team discovered that under certain circumstances subatomic particles such as electrons are able to instantaneously communicate with each other regardless of the distance separating them. It doesn’t matter whether they are 10 feet or 10 billion miles apart. Somehow each particle always seems to know what the other is doing. The problem with this feat is that it violates Einstein’s long-held tenet that no communication can travel faster than the speed of light. Since traveling faster than the speed of light is tantamount to breaking the time barrier, this daunting prospect has caused some physicists to try to come up with elaborate ways to explain away Aspect’s findings. But it has inspired others to offer even more radical explanations.

University of London physicist David Bohm, for example, believes Aspect’s findings imply that objective reality does not exist, that despite its apparent solidity the universe is at heart a phantasm, a gigantic and splendidly detailed hologram.

…

This insight suggested to Bohm another way of understanding Aspect’s discovery. Bohm believes the reason subatomic particles are able to remain in contact with one another regardless of the distance separating them is not because they are sending some sort of mysterious signal back and forth, but because their separateness is an illusion. He argues that at some deeper level of reality such particles are not individual entities, but are actually extensions of the same fundamental something.

David Icke has been saying for years that our reality is a holographic projection, an illusion, a virtual reality simulation and nothing more. Thomas Campbell describes the same thing in his book trilogy “My Big TOE.” Karl Pribram, a neurophysiologist at Stanford University and author of the classic neuropsychological textbook “Languages of the Brain,” eventually came to the same realization, as Talbot mentions in his book:

As for Pribram, by the 1970s enough evidence had accumulated to convince him his theory was correct. […] The question that began to bother him was, If the picture of reality in our brains is not a picture at all but a hologram, what is it a hologram of?

Pribram realized that if the holographic brain model was taken to its logical conclusions, it opened the door on the possibility that objective reality—the world of coffee cups, mountain vistas, elm trees, and table lamps—might not even exist, or at least not exist in the way we believe it exists. Was it possible, he wondered, that what the mystics had been saying for centuries was true, reality was maya, an illusion, and what was out there was really a vast, resonating symphony of wave forms, a “frequency domain” that was transformed into the world as we know it only after it entered our senses?

Even Albert Einstein is often famously quoted for saying that “reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.”

Could our reality really be a holographic simulation on a grand scale, running inside a cosmic computer, and are we just taking part in this simulation to evolve our consciousness, as Campbell suggests in his books? Are we going to wake up in some kind of classroom when we die and find out we’ve just completed another lesson in the education/evolution of our consciousness? That our reality has to be some kind of computational simulation is evidenced by its fractal nature — a dead giveaway. It appears that the famous comedian George Carlin was right on the money when he called our world “the big electron,” and comedian Bill Hicks equally as right when he called it “just a ride.”

Like Michael Talbot says:

This striking new picture of reality, the synthesis of Bohm and Pribram’s views, has come to be called the holographic paradigm, and although many scientists have greeted it with skepticism, it has galvanized others. A small but growing group of researchers believe it may be the most accurate model of reality science has arrived at thus far. More than that, some believe it may solve some mysteries that have never before been explainable by science and even establish the paranormal as a part of nature. Numerous researchers, including Bohm and Pribram, have noted that many para-psychological phenomena become much more understandable in terms of the holographic paradigm. In a universe in which individual brains are actually indivisible portions of the greater hologram and everything is infinitely interconnected, telepathy may merely be the accessing of the holographic level.

And the last part is precisely what Thomas Campbell has explored in great detail in his book trilogy “My Big TOE.” I think Campbell has come the closest to a unified theory of everything than anyone has ever been before. But Campbell is just one of the growing number of scientists, along with Nassim Haramein and others, who are all contributing their piece of the puzzle in what Talbot calls the holographic paradigm — a new, more complete and much more accurate scientific model of our reality. Moreover, the realization that everything in our reality is fundamentally interconnected and part of a larger whole, will encourage us to look for solutions to problems in a new way. Like Bohm said:

Thought processes and quantum systems are analogous in that they cannot be analyzed too much in terms of distinct elements, because the intrinsic nature of each element is not a property existing separately from and independently of other elements, but is instead a property that arises partially from its relation with other elements.

This is the built-in feedback loop that is a fundamental characteristic of fractals which I mentioned at the beginning of this post, and in my opinion one of the most important things to realize. Our reality defines us, but we can also give feedback and influence our reality. As Talbot further explains in his book:

Indeed, Bohm believes that our almost universal tendency to fragment the world and ignore the dynamic interconnectedness of all things is responsible for many of our problems, not only in science but in our lives and our society as well. For instance, we believe we can extract the valuable parts of the earth without affecting the whole. We believe it is possible to treat parts of our body and not be concerned with the whole. We believe we can deal with various problems in our society, such as crime, poverty, and drug addiction, without addressing the problems in our society as a whole, and so on. In his writings Bohm argues passionately that our current way of fragmenting the world into parts not only doesn’t work, but may even lead to our extinction.

Interestingly, this is exactly what industrial designer, social engineer and futurist Jacque Fresco — who I believe is the social Nikola Tesla of our time — mentioned in his books titled “The Best that Money Can’t Buy” and “Designing the Future”. Fragmenting the world into parts will prevent us from making real and lasting progress in our evolution and development. Fresco’s approach to a new world system takes into account the fact that we have to look at our world as a whole if we want to arrive at solutions that can safely take us far into the future. Both Fresco and Bohm find support in famous astrophysicist Carl Sagan, who once said: “A new consciousness is developing which sees the earth as a single organism and recognizes that an organism at war with itself is doomed.” And let’s not forget Nikola Tesla, who said: “When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is, all things being particles of a real and rhythmic whole.“

There’s absolutely no doubt in my mind that fundamentally understanding the fractal nature of our universe holds great promises for our future. Once we understand that we’re all one, that all things are infinitely interrelated and influencing each other — and this understanding is now backed by science — we may start to work towards a global society where this scientific fact is reflected everywhere throughout.

Comments

There are 11 responses. Follow any responses to this post through its comments RSS feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.