Swadeshi and Swaraj according to Gandhi

While reading the book “The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism” by Jeremy Rifkin (highly recommended), I came across a very interesting part where Rifkin discussed some social concepts that were being promoted by Gandhi during his time. First I want to quote the relevant parts from the book, and then I’m going to comment on why I think this is interesting. Here’s from Rifkin’s book:

Gandhi’s views ran counter to the wisdom of the day. In a world where politicians, business leaders, economists, academics, and the general public were extolling the virtues of industrialized production, Gandhi demurred, suggesting that “there is a tremendous fallacy behind Henry Ford’s reasoning.” Gandhi believed that mass production, with its vertically integrated enterprises and inherent tendencies to centralize economic power and monopolize markets, would have dire consequences for humanity.46 He warned that such a situation would be found

‘to be disastrous. . . . Because while it is true that you will be producing things in innumerable areas, the power will come from one selected centre. . . . It would place such a limitless power in one human agency that I dread to think of it. The consequence, for instance, of such a control of power would be that I would be dependent on that power for light, water, even air, and so on. That, I think, would be terrible.’47

Gandhi’s alternative proposal was local production by the masses in their own homes and neighborhoods—what he called Swadeshi. The idea behind Swadeshi was to “bring work to the people and not people to the work.”49 He asked rhetorically, “If you multiply individual production to millions of times, would it not give you mass production on a tremendous scale?”50 Gandhi fervently believed that “production and consumption must be reunited”—what we today call prosumers—and that it was only realizable if most production took place locally and much of it, but not all, was consumed locally.51

Gandhi’s ideal economy starts in the local village and extends outward to the world. He wrote:

‘My idea of village Swaraj is that it is a complete republic, independent of its neighbors for its own vital wants, and yet interdependent for many others which dependence is a necessity.’52

He eschewed the notion of a pyramidically organized society in favor of what he called “oceanic circles,” made up of communities of individuals embedded within broader communities that ripple out to envelop the whole of humanity. Gandhi argued that

‘independence must begin at the bottom . . . every village has to be self-sustained and capable of managing its affairs even to the extent of defending itself against the whole world. . . . This does not exclude dependence on and willing help from neighbours or from the world. It will be a free and voluntary play of mutual forces. . . . In this structure composed of innumerable villages, there will be ever widening, never ascending circles. Life will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom. But it will be an oceanic circle whose center will be the individual. . . . Therefore the outermost circumference will not wield power to crush the inner circle but will give strength to all within and derive its own strength from it.’53

For Gandhi, happiness is not to be found in the amassing of individual wealth but in living a compassionate and empathic life. He went so far as to suggest that “real happiness and contentment . . . consists not in the multiplication but, in the deliberate and voluntary reduction of wants,” so that one might be free to live a more committed life in fellowship with others.55 He also bound his theory of happiness to a responsibility to the planet. Nearly a half century before sustainability came into vogue, Gandhi declared that “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need but not enough for every man’s greed.”56

One of the reasons why this caught my attention is because through my own research, some of which can be found in my article on The Cycle of Life, I had already come to the conclusion that the best way to develop and organize a truly sustainable social system was to do so around the individual, taking into account his basic natural needs, and proceeding from there. In fact that’s what true love essentially is — respecting every individual’s right to life, or in other words, respecting their sovereignty. So not only should “every village be self-sustained and capable of managing its affairs even to the extent of defending itself against the whole world,” but every individual should be able to do all of that as well. A strong society derives its strength from the strength of the individuals that make up that society.

Like Gandhi I also came to the conclusion that in such a social system, there can be no centralized authority, and that authority should be evenly distributed throughout the system:

Based on this, it’s very important to note that there is no central point of authority in our physical reality; the number 9 is distributed throughout the whole system. This is a very important mathematical fact that shows that nature is fundamentally a distributed system, a peer to peer (P2P) system with no central point of authority. The number 9, which is the source and authority of this whole system, is distributed everywhere throughout the system, in the parts and in the sum of all parts. If we want to create a truly prosperous and healthy human society on Earth for the long term, we’ll have to model it after this important fundamental understanding (so no governments and no central authorities whatsoever, but anarchy).

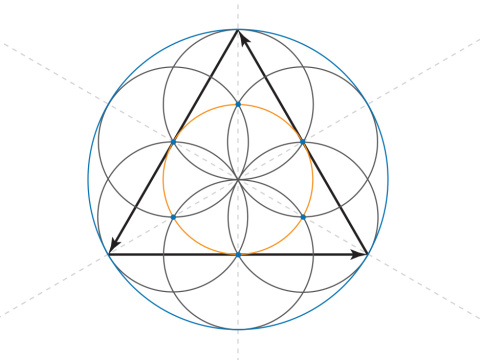

So indeed, there’s no vertical distribution of power or authority, but lateral distribution; there are no hierarchies just like in Gandhi’s idea of Swaraj. And if you take a look at what Gandhi mentioned about “oceanic circles,” made up of communities of individuals embedded within broader communities that ripple out to envelop the whole of humanity, I’m sure you’ll immediately see the similarity with the Seed of Life, as discussed in my Cycle of Life post.

This is how the universe is fundamentally organized, and I thought it was quite awesome to find out that Gandhi also came to the same conclusions long ago. I wonder if he also knew about the basic geometry that’s behind these ideas, and if this was also the foundation for his reasoning.

Comments

There are 0 responses. Follow any responses to this post through its comments RSS feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.